This article runs in a section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, regenerative economy we need from Alaska to central California. Magic Canoe and the Salmon Nation Trust fund this project.

About 33 billion pounds of plastic enter the world’s oceans every year.

Canada contributes approximately four million tonnes of plastic waste annually, according to Oceana Canada, an ocean conservation advocacy charity. About half of that is single-use plastics like food packaging.

Nationally, less than 10 per cent of that waste will be recycled, while the rest is sent to landfills or incinerators — or becomes litter.

No matter the intended final destination, plastic can end up in the oceans, says Anthony Merante, senior campaigner for plastics with Oceana Canada. Shipped recyclables or cargo lost at sea, garbage carried out of a landfill by the wind — the ocean is their final frontier.

“A plastic bag is very commonly mistaken as jellyfish, so whales, dolphins, sea turtles will ingest them,” he told The Tyee.

Hard plastics and polypropylene ropes can entangle or strangle ocean wildlife, while plastic tarps and other large items can block the sun, killing coral habitats.

Then there’s the “ever-dreaded microplastics,” Merante said, created by the UV and physical degradation of plastics. Microplastics can be ingested by wildlife of nearly all sizes and kinds, including humans.

“Things like tuna or salmon eat them, and then we catch those fish, eat them, that plastic pollution goes from the environment onto our plate, and into our bodies,” he said.

But one B.C.-based non-profit has found a downstream pollution solution: recapture, recycle, and recirculate reconstituted discarded plastic back into the market to become sustainable, responsible consumer goods.

Since 2013, Ocean Legacy Foundation has trained 200 people across B.C. in shoreline and on-the-water plastic cleanups, from lighters and tennis balls to so-called “ghost gear”: fishing nets, traps, buoys, and rope left adrift by fishers and industry. They also accept waste collected by industry.

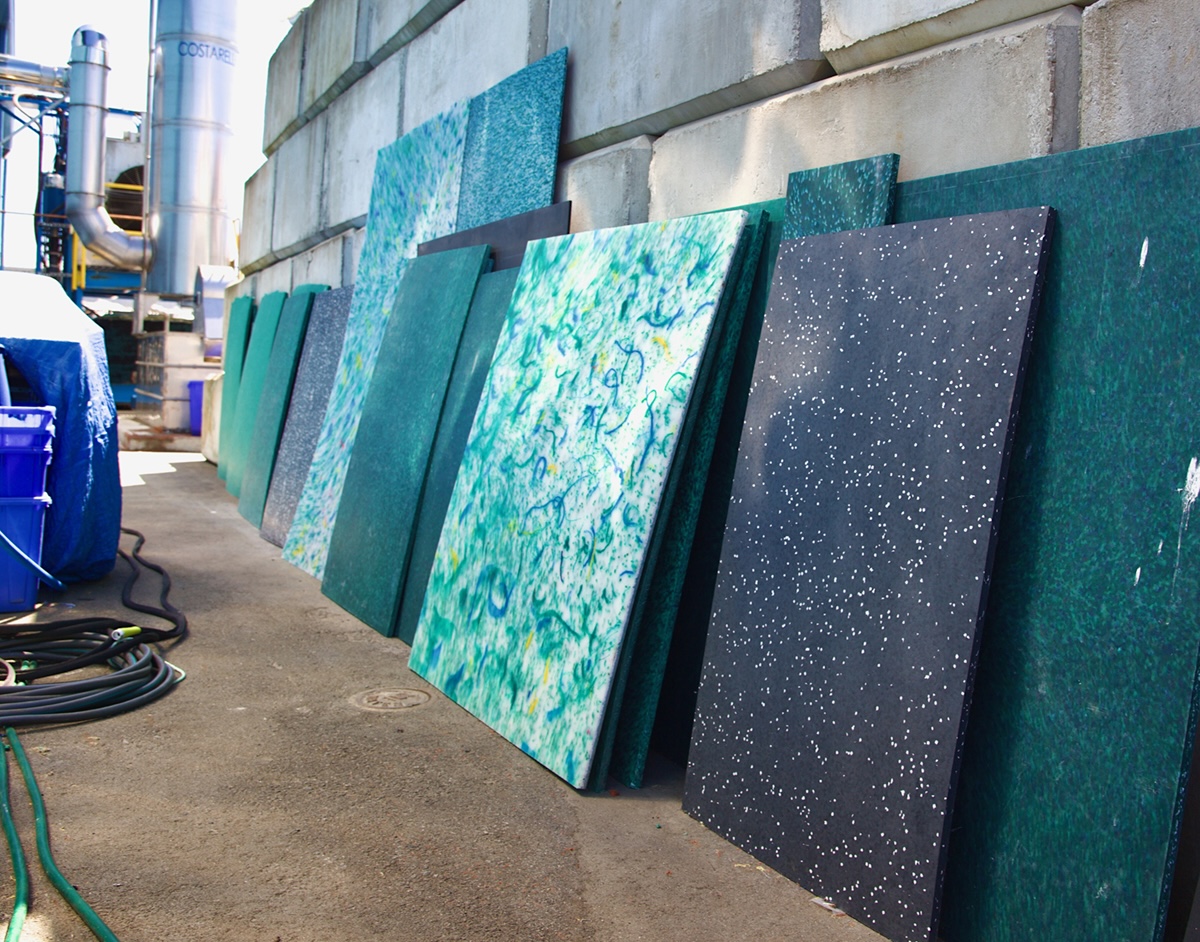

The recaptured plastics go to Ocean Legacy’s Richmond recycling facility, where for the last four years ocean plastic has been sorted, shredded, melted, extruded, and diced into pellets, which are marketed as Legacy Plastic to manufacturers of plastic products.

The Richmond facility houses the first and largest marine waste recycling program of its kind in Canada.

It was important to Ocean Legacy that it sell Legacy Plastic only to companies making durable products — such as deck furniture, construction lumber, and tower planters — that can be collected and recycled again at the end of their lifespans, says Chloé Dubois, Ocean Legacy’s co-founder and executive director.

Though Legacy Plastic is a private business, plastic recycling needs public support through government grants like B.C.’s Clean Coast, Clean Waters fund, and the federal Ghost Gear fund, neither of which were renewed in 2025.

“Right now, without government grants, we’re bringing in less than 50 per cent of what we need to sustain the operation through the revenue of the [recycled] plastics,” Dubois told The Tyee.

“And at this point, they either have to create policy mechanisms to support the growth of the recycled plastic market, or they need to provide subsidies, because it’s such a tough world out there.”

Ocean Legacy diverts 11 different plastic types from the waste stream, collected through its own cleanups, from community partners at seven different B.C. landfills, and directly from marine industry partners, who typically collect mass volumes of plastic waste they ship directly to Ocean Legacy.

Until this year, the province’s Clean Coast, Clean Waters program provided Ocean Legacy with funding for shoreline cleanups, allowing the non-profit to create a network of people trained in ocean plastic cleanups along B.C.’s Pacific coastline.

Ocean Legacy accepts marine-related plastics like Styrofoam-filled tires, buoys, oyster baskets, and crab pots, foam floats, netting, barrels, rope, hard plastic fragments, and Styrofoam, and beverage containers.

What Ocean Legacy can’t recycle — stuff like tennis balls, chip bags, lighters, PVC pipe, metal, wood, and glass — is stored on site until it has collected enough to send to other recyclers in the Lower Mainland.

Inside its Richmond warehouse, plastics that Ocean Legacy recycles are divided into two streams: fibre and hard ribbon.

The hard-ribbon stream is put through an industrial shredder before being washed, dried and fed into an extruder that melts and forms it into long strands the diameter of a drinking straw. Then it’s cooled in water and chopped into pellets.

The fibre stream, which includes objects such as rope, goes through a guillotine shredder before feeding into a densification process that turns it into what Dubois refers to as a “crumble.” Then it goes through the extruder and pelletization process.

Three pellet “supersacks” of 700 kilograms are produced each day, with Ocean Legacy moving towards its goal of processing a tonne of plastic waste per hour.

Not every manufacturer wants Ocean Legacy’s pellets, however. During The Tyee’s visit there were massive sacks upon sacks — 550 kilograms each — of shredded polypropylene nylon rope, for example, ready to be shipped off to manufacturers to make new rope or other textiles, even carpet.

Outside, Ocean Legacy has a tire guillotine used to chop up and separate the Styrofoam-filled rubber tires, which are often used in dock construction. That way, both the rubber and the Styrofoam can be recycled.

Ocean Legacy also has an on-site lab, which can be used to identify different kinds of plastic when they’re not sure what they’ve recovered.

Moving solutions upstream

While Legacy Plastic is an end-of-the-line plastic waste solution, Ocean Legacy is flowing change upstream, too, through its EPIC program: education, policy, infrastructure and cleanup.

Working with governments of all levels — settler and Indigenous — EPIC promotes measures to prevent plastics from ending up in the ocean in the first place.

The program offers online curriculums on the ocean plastic problem’s origins, impacts, and solutions. EPIC also shares research reports to influence government policy, promotes the implementation of zero-waste strategies to force plastic producers to reduce or eliminate single-use plastics, and helps develop best practices and strategies for shoreline cleanups.

Ocean Legacy, which recently began collecting marine plastics from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, is at work on a national policy to collect and manage marine debris across Canada’s coasts.

There are some differences in the materials collected out east versus west, Dubois said, and adapting to the realities and needs of the ocean plastic problem based on location is an important part of its expansion pilot.

“Out in the Maritimes, we find a lot more ropes with leaded cores,” for example, Dubois said.

Ocean Legacy also makes its lab available to other recycled plastic product makers to help answer key questions, such as how much recycled material can be incorporated into a new product before its physical integrity is meaningfully affected.

Is recycling enough?

Recycling alone won’t save the oceans from the steady supply of plastic pollution, especially when recyclers focus on polymer plastics, Oceana Canada’s Merante said.

British Columbia has high rates of recycling, with Recycle BC announcing an 83.3 per cent recovery rate in 2024 for its residential packaging and paper recycling program, with 80 per cent of recycling materials going to North American end markets and 99 per cent of plastics collected processed in B.C.

But Merante said we don’t know how much of what’s collected nationally is actually recycled.

As an example, he cited B.C.’s garbage incinerators, such as the one in Burnaby, which burn plastic along with other waste for energy production, as well as the Richmond Lafarge cement plant that was burning non-recyclable plastics for fuel as recently as 2019.

Canadian plastic and waste are also sent to other countries for processing — often by ship, where waste can fall into the waves.

“We’re calling on governments and industries to stop pushing this false narrative that we can recycle our way out of the problem,” Merante said.

Instead, Oceana Canada would like to see plastic production cut down at the source through stricter regulation of single-use plastic products.

Currently Canada has outlawed the “manufacture, import, and sale of single-use plastic checkout bags, cutlery, foodservice ware made from or containing problematic plastics, ring carriers, stir sticks, and straws.”

In 2023 the Federal Court ruled the national single-use plastics ban was “invalid and unlawful,” though the Federal Court of Appeal has issued a stay motion while Canada appeals this ruling.

Oceana Canada wants even stronger federal and provincial regulations over the manufacturing and sale of any new or “virgin” plastics, not just the single-use ones, emulating jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany, where they have either passed laws limiting the use of virgin plastics or banned specific single-use plastics beyond what Canada has already outlawed, Merante added.

While lauded for their environmental impacts, single-use plastic bans have been criticized for discriminating against people with disabilities who require straws for consuming beverages. Alternatives like reusable straws must be carried with you and require cleaning between uses, while paper straws can become soggy long before your drink is finished.

For her part, Dubois doesn’t think recycling has failed.

“Recirculating resources is fundamental and is a lesson right from nature’s playbook,” she said.

Instead, she points to the mass production of new plastic as a key problem. Right now, she said, new plastics are cheaper to buy than recycled materials like Legacy Plastic because of government oil and gas subsidies.

But while subsidizing recycled plastics in turn would be “helpful,” Dubois said Ocean Legacy has other ideas — such as adding a recycling rebate for returning a broader selection of plastic waste.

Where Oceana Canada and Ocean Legacy agree is that the circular economy won’t save us from our ongoing plastic crisis without policy change.

Clean Coast, Clean Waters program under review

In the current climate, the reality is that organizations such as Ocean Legacy also require reliable, sustainable funding to support the collection, recycling, and recirculation of plastics.

Ocean Legacy received both federal funding, through Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Ghost Gear program, and provincial funding, through the Clean Coast, Clean Waters program, as recently as last year. But neither program provided funding this year.

In an email to The Tyee, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Parks told The Tyee the Clean Coast, Clean Waters program is undergoing a review. As a result, no 2025 funding was provided.

Similarly, funding for the federal Ghost Gear program, which invested $58.3 million in 143 projects that removed 2,474 tonnes of ghost fishing gear between 2019 and 2024, was not renewed in 2024-25, according to an emailed statement from Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

The impact from the loss of funds on Ocean Legacy has been substantial.

“It has been tough, and we’ve had to do layoffs,” Dubois said.

But she sees a future where Ocean Legacy’s work acts as a bridge between the blue economy — the reaping of resources from, and the preservation and regeneration of, the marine environment — and the circular economy of a greatly reduced reliance on using virgin plastics in favor of recycling and reusing what plastic already exists.

“What I would like to see with this facility is that it does become a tool to reinvest back into communities,” Dubois said, a kind of hub for training, skill building, and physical infrastructure for communities invested in the blue economy in the Pacific Northwest.

This includes incentivizing the return of certain marine plastic equipment, similar to B.C.’s Extended Producer Responsibility policy where plastic producers are required to invest in their products’ end-of-life waste management, instead of expecting communities to cover the costs.

“This would ensure that consistent annual core funding is generated to support the waste management system that is needed to collect, collate, transport, and process these materials,” Dubois said, as well as providing a small financial incentive for people to recycle these plastics.

Until that happens, Ocean Legacy is making do on a blended finance model of government funding, private investment, donations, sponsorships, and nature-based or carbon credits. Its ultimate goal is to do such a good job working with industry to eliminate plastic waste in the ocean that ocean and shoreline cleanups are no longer necessary.

“It is possible, but the investment and political will on a national scale are critical,” said Dubois.