Story by Serena Renner

Photographs by Bennett Whitnell

This article is from bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and regeneration powered by the California Academy of Sciences.

Editor’s Note: Magic Canoe supports reporting like what you’ll find here because it shows the depth and breadth of Salmon Nation in all its grandeur—the rich, bioregional fecundity, the ways various stakeholders work together to heal relationships between themselves and the land and water, the capacity to forge ahead with practical solutions that work for both the region’s economy and ecology. The following feature illustrates what wilderness, Indigenous sovereignty, and reconciliation looks like when we not only imagine a viable future, but live into it. We hope you enjoy.

The ocean bumps beneath our boat, and a cold mist obscures the way forward. I peer over the driver’s shoulder to consult the GPS screen behind the steering wheel. The map reveals a labyrinth of islands, as well as dozens of inlets and fjords cutting up the western fringe of British Columbia’s Central Coast. Most bear colonial names: Jackson Passage, Laredo Inlet, Princess Royal Channel. But looking closer, I can make out other, older names: Nowish, Khutze, Kynoch.

When the mist lifts, the topography pops up all around me. Sheer granite peaks plunge into a Magic Eye mirage of cedar, fir, and spruce trees rooted to rocky shores. Some islands have stories and names that match their shapes—navigational aids before nautical charts, teachings before written language. Our boat, Ksm Wüts’iin (Mouse Woman) passes Qweeqweea’dzee (Upside-Down Canoe), which gets its name from a legend about animals working together from their shared canoe to fight a sea monster. It’s a story that holds particular resonance today.

Finally, we reach Kynoch Inlet, the site of today’s crab survey. According to oral history, Kynoch is the birthplace of the Xai’xais Nation. The story goes that Raven searched for the perfect place for the people to be born and settled on Kynoch for its bounty and biodiversity. It had just the right mix of plants and trees; snow-fed rivers; and bays rich in marine life, from salmon and rockfish to clams, cockles, and crabs. The Xai’xais amalgamated with the Kitasoo Nation about 150 years ago, and Kynoch Inlet is now one of six areas in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory where recreational and commercial crabbing is off limits to protect Indigenous access.

Ken Cripps cuts the boat’s engine and flips on a winch. With a rumbling whir, the machine hauls a length of rope from the water until the first trap appears. Two small Dungeness crabs (Metacarcinus magister) click their claws inside. Cripps—the exuberant marine advisor to the Kitasoo Xai’xais Stewardship Authority, who some call Ken Crabs—cocks his head, surprised by the low catch. In these bountiful waters, the survey team can usually count on reaching the nation’s measure of a successful catch: roughly seven adult male crabs per trap. (Any trapped females are released.) Three colleagues record the sex, shell size, and shell condition of the two females before flinging them into the sea.

A few dozen meters away, the stewardship crew repeats the process for a second trap. When it surfaces, it’s empty save for two sea stars. Cripps holds them over his chest as if he’s a mermaid, and everyone laughs. Then the boat driver puts on the Alanis Morissette song “Ironic,” as if to emphasize the unexpectedly low catch in an area known for its productivity.

It’s true that the ocean off the Central Coast is some of the richest in the world. Shifting currents of cold, nutrient-filled water bring copious plankton and fish. In turn, those smaller life forms fuel more than 20 species of marine mammals, including humpback whales that corral prey inside nets of bubbles before inhaling them in a single baleen-gummed gulp. In the deeper waters, rare coral and glass sponge reefs support such species as shortraker rockfish and ruby octopus, while shallower kelp forests and eelgrass meadows shelter culturally important herring, crab, and all five species of Pacific salmon.

Yet here, as in so many other places, stressors like overfishing and climate change are threatening this productivity and the ways of life that depend on it. Around the Central Coast, marine species including Dungeness crab, coho salmon, and northern abalone have sharply declined, while those like eulachon have all but vanished. In response, the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation—like many other Indigenous peoples here and around the world—have been working to take ocean management back into their own hands.

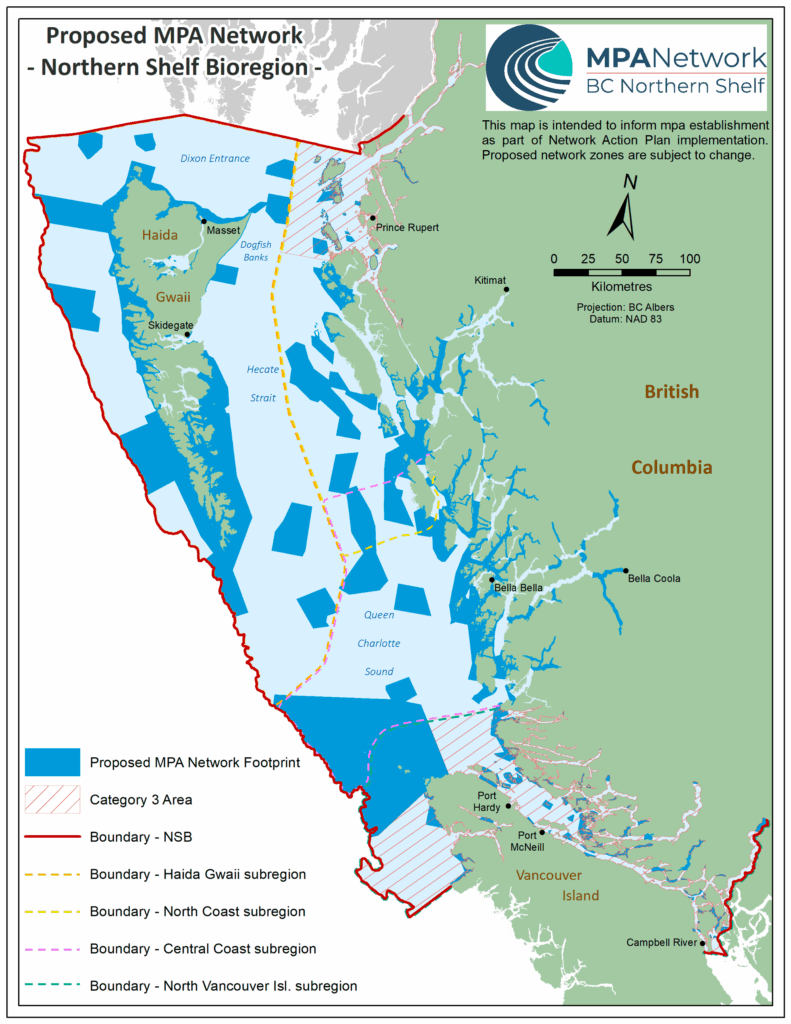

Over the past two decades, British Columbia has made strides in recognizing Indigenous sovereignty, and Indigenous-colonial relationships that had long been antagonistic have become more cooperative. Yet most of the progress has occurred in terrestrial environments. Now, a new network of marine protected areas (MPAs) in a region known as the Great Bear Sea is trying to bring strategies that have worked on land into the ocean. The plan is to connect ecological hotspots that will act like underwater stepping stones between B.C.’s northern Vancouver Island and Alaska.

While many of the protected areas are still in the works, one that’s well underway is the Central Coast National Marine Conservation Area Reserve (the Central Coast MPA), which includes Kynoch Inlet. Set to be established around 2027, it will be the largest of the Great Bear Sea’s conservation areas, which together will cover a footprint nearly the size of Belgium.

Beyond its biodiversity and size, the governance structure will set the Great Bear Sea apart. It’s the first marine area in Canada—and one of few places, land or sea, in the world—designed to be collaboratively managed by three levels of government: federal, provincial, and Indigenous, as represented by 17 coastal First Nations. “It’s a laudable, progressive project for the recognition of Indigenous rights and title,” says Michael Bissonnette, a lawyer on the marine team at West Coast Environmental Law, a firm based in Vancouver, B.C. If done right, the network “could be a real, meaningful model for reconciliation elsewhere.”

The changes have been a long time coming, and the way forward isn’t fully clear. But the mist is lifting, revealing not just the lay of the land (and sea), but the benefits of working together to protect the whole ecosystem.

Roughly 500 kilometers (310 miles) north of Vancouver and accessible only by seaplane or boat, the village of Klemtu is a confluence of cultures. Old metal herring skiffs bob next to colorful sailboats, while wooden signs point in the directions of Prince Edward Island, Hawai‘i, and Australia. Residents—the vast majority of whom are Indigenous—display window signs showing clan identities like raven family crests alongside sporting loyalties, often to the Vancouver Canucks. Streets are named after animals and translated into Sgüüxs, the native language of the Kitasoo people, while stop signs come in Sgüüxs as well as Xai’xais: requiring drivers to gyiloo or h̓úkváxsi.

Klemtu is the home base of the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, and it’s where I meet Doug Neasloss, the nation’s elected chief, at the stewardship offices. On this Friday afternoon, the modular building is busy with staff changing in and out of dive gear. The department has around 40 employees; more than half are from the nation and the other half are gumshwa, meaning non-Indigenous or, literally, driftwood. Neasloss meets me in the conference room and sits down at the live-edge table.

Now age 42, with 14 years as elected chief under his belt, Neasloss is canny yet casual, quick with a strong argument or a wry joke. When I ask how long his nation has been managing their own food fishery, he doesn’t miss a beat. “Thousands of years,” he deadpans. I was thinking of modern management since colonization, but point taken. I apologize, feeling like a real gumshwa, and rephrase the question.

To understand Indigenous co-governance of the ocean, Neasloss explains, it helps to know something about the history of co-governance on land, starting with the land we’re meeting on. The place known as Klemtu, on the eastern edge of what’s now called Swindle Island, was once a seaweed-strewn trading camp where the Kitasoo people of the islands exchanged delicacies like herring roe for crab apples and mountain goat fat from the Xai’xais people of the mainland. Chiefs from both nations managed resources, passing down a conservation ethic centered on taking only what you need.

Feeding the community from the local harvest was incentive for sustainable management. While there are a few examples of Indigenous mismanagement in the northeast Pacific—such as oral history about the Haida people of Skidegate fishing eulachon to local extinction long before colonization—these mistakes are often incorporated into stories and lessons aimed at changing future behavior. Far more common is historical evidence of sustainable practices, from using specially designed hooks to target only midsized fish to dismantling fish traps after harvest to prevent overexploitation.

Through such systems, First Nations on the Central Coast kept their lands and waters largely in balance for at least 14,000 years. Then came the onslaught of colonization and diseases like smallpox that decimated Indigenous populations.

In 1763, the British monarchy wrote a proclamation that recognized First Nations’ land title, or ownership, to Indigenous-occupied areas throughout North America. But in B.C., newly-formed colonial governments largely ignored this precedent. Most of the 200-plus First Nations in the province, including Kitasoo Xai’xais, never signed treaties giving up their land or sovereignty, yet beginning in the mid-1800s, Canada forced Indigenous peoples onto small reserves and implemented policies that deliberately severed connections to their lands, waters, cultures, and traditional governance. Since then, more than three-quarters of B.C. forests have been logged and 90 percent of some marine species overfished. Settlers reaped the benefits, and Indigenous communities were left struggling with basic needs, from housing to healthcare.

This is how Neasloss—whose Indigenous name, Muq’vas Glaw, translates to White Bear—remembers Klemtu in the 1990s. He also remembers it as a meeting place where people came together to talk about logging. In the late ’90s, the B.C. government issued licenses to clear-cut swaths of Kitasoo Xai’xais territory, part of the world’s largest remaining coastal temperate rainforest and home to rare animals like wolverines and “spirit bears,” black bears with recessive genes for white fur. Forestry companies had offered 100 jobs in a town that was then home to around 300 people. But although some residents were intrigued, Kitasoo Xai’xais leaders didn’t have much interest in logging; they were already exploring tourism as an economic alternative. So the chiefs invited timber execs and environmentalists to Klemtu to hash out a solution.

Around the same time, Indigenous leaders from the northern tip of Vancouver Island to the border of Alaska—an area that would soon be dubbed the Great Bear Rainforest—began getting together, too. They convened to discuss their shared socioeconomic challenges as well as a common desire to resume their own resource management and be treated as equals to settler governments. More than a dozen First Nations formed alliances to raise a more unified voice. “We agreed to start dropping our borders and collaborate more,” Neasloss says.

Over more than two decades, these alliances—along with the province, environmental groups, and timber companies—hammered out agreements to protect and manage the Great Bear Rainforest. It was a landmark success for conservation and a springboard for co-governance, or the sharing of power and decision making, between the provincial government and First Nations. The agreements protected more than two-thirds of the remaining old-growth forest in the area, provided CAD $120 million in funding, helped launch a tourism industry for Kitasoo Xai’xais, and eventually served as a blueprint for future protection, economic development, and collaboration in the adjoining Great Bear Sea.

In 2017, B.C. banned grizzly bear hunting at coastal First Nations’ behest. A few years later, the province recognized the Kitasoo Xai’xais ban on hunting black bears, the progenitors of white spirit bears. BC Parks also worked with nations on the Central Coast to start a joint enforcement program for stewards known as guardians—the Indigenous version of a park ranger or a coast guard. Guardians who pass the province’s ranger training now have authority to enforce both British Columbian and Indigenous laws in provincial parks, and they’re the main eyes and ears monitoring the Central Coast today.

Despite all the progress on land, though, marine areas in Canada are still largely controlled by the federal government, which has historically been less open to collaborating with First Nations about fisheries and ocean policy. B.C. officials have spent more than a decade drafting plans with 17 First Nations to try to replicate the success of the Great Bear Rainforest into an MPA network, but the province’s jurisdiction is limited to land and some nearshore areas. Out at sea—from the sponge-studded reefs to the herring-rich kelp forests—Canada’s federal ministers still rule the waters. And until recently, they’ve been reluctant to get in the shared canoe.

As soon as Ksm Wüts’iin reaches the Klemtu dock, the team gets to crushing and dismembering the live male Dungeness crabs that they’ve caught and catalogued as part of the day’s survey work. Cripps shows me his technique: punching the crab’s carapace against a T-shaped dock cleat and then grabbing all eight legs—four in each hand—for a sharp twist that simultaneously breaks off the crab’s legs and launches its shell into the sea.

Amid crab-scented carnage, Cripps and his colleagues recount how, after those first few empty pots, they pulled up heftier loads from the Kynoch Inlet shallows, where the crabs probably followed the carcasses of spawning salmon. Another fisherman on the dock fires up a camp stove for an impromptu after-work crab boil, and Cripps offers a Ziploc bag of meaty legs to an elderly gentleman watching from the pier above. “Want some crab?” Cripps hollers. “Oh yeah!” the man lights up, before moseying down to collect his dinner.

“When people ask, How important is the sea? It’s like asking, How important is the place you get all your food?” says Haay-maas (Ernest Mason Jr.), a Kitasoo Xai’xais elder and hereditary chief (a title inherited under the nation’s traditional governance system) who goes by Charlie. He gives the example of Gitdisdzu Lugyeks (Kitasu Bay), which hosts one of the coast’s largest remaining runs of herring each spring. With the herring come their delicious roe, along with the big fish that eat the small fish—halibut, red snapper, lingcod, and spring salmon. Spring salmon then feed killer whales, as well as wolves, bears, and eagles. “That one little herring is so darn important,” Haay-maas says. “It’s not only important to us, it’s important to everything else that comes to feed. We need to protect it.”

To Haay-maas and others familiar with Indigenous resource management, First Nations’ millennia-long track record speaks for itself. And given their holistic understanding of the ecological threads connecting everything from the mountaintops to the seafloor, Indigenous elders have long advocated to extend the protections of the Great Bear Rainforest out to sea. Yet until recently, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)—the federal agency that oversees marine species—balked at letting First Nations make decisions.

In the early 2000s, around the same time that First Nations were working with the B.C. government to more cooperatively manage terrestrial resources, Indigenous fishers on the Central Coast began noticing they were pulling up only around one-quarter of the crabs they used to catch. Kitasoo Xai’xais, along with three neighboring First Nations—Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv, and Nuxalk—petitioned the federal government to close some areas to commercial and recreational crabbing to preserve their traditional food, social, and ceremonial rights, which are enshrined in Canada’s constitution. DFO denied the request.

So in 2014, the four nations embarked on a joint study to try to make their case. Using DFO’s own methods, they compared 10 bays and channels that First Nations had closed to nontraditional uses under their own authority—which wasn’t recognized by the federal government but was mostly respected by commercial and recreational fishers—against 10 bays left open to all kinds of fishing. Unsurprisingly, more adult male crabs were found at closed sites than at open ones. But because the results didn’t necessarily prove that crab shortages were affecting First Nations’ ability to feed themselves, the group then had to commission a research team to interview 38 Indigenous crabbers about current and historical catches as well as household needs.

The survey confirmed what the nations had been saying all along; it just repackaged Indigenous stories into a scientific paper. “The burden of proof is always on First Nations and never on the Canadian government,” Cripps says. “That’s what needs to shift.”

By the mid-2010s, things were starting to change. Justin Trudeau, who campaigned on promises to recognize Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, was elected Canada’s prime minister; Canada signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; and in 2019, B.C. became the first government on Earth to enshrine that declaration into law. That same year, eight coastal First Nations signed a reconciliation agreement with the federal government that included promises for “transformative change in the collaborative governance” of fisheries. This agreement cemented the Dungeness crab project as a model of co-governance and ultimately closed 28 historical crabbing areas to non-Indigenous fishing.

“It became less about the crab and more about the process,” recalls Colin Masson, a retired DFO director who was involved in the reconciliation agreement and the crab pilot project. While DFO prefers to manage species like Dungeness crab on larger regional scales, “the argument for closures in specific areas was profound,” Masson says. The four nations—including the Ksm Wüts’iin survey team—now work with DFO to monitor these sites.

Because Dungeness crabs reach sexual maturity after just two years, some of these areas are already rebounding, aligning with new research that shows that MPAs with shared governance are more effective at increasing populations of marine species. In fact, a study from early 2025 finds that the type of governance in an MPA is even more important for boosting fish biomass than the level of protection.

“If you find ways to work together, you can achieve more,” Masson says. “A collective decision that we all agree on is going to be stronger than an individual decision.”

Back on the Klemtu waterfront, the evening sun dips behind a nearby island while the last fishers and scientists pack up for the night. In the dimming light, I can make out a white sign above the dock stating that six bays in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory—including Kynoch Inlet—are now officially closed to commercial and recreational crabbing. It’s just one sign of a victory that seems small but has cleared the way for joint management of other marine species. And it’s helping shape the future of the Central Coast MPA and the larger Great Bear Sea network.

A few months before my visit to the Central Coast—on June 25, 2024—federal, provincial, and Indigenous leaders gathered together at the Vancouver Convention Centre to announce the Great Bear Sea agreements. The Coast Mountains and Burrard Inlet glistened behind glass windows. Neasloss was seated stage left in a black vest and funky red-and-black tie, surrounded by his cohort of Indigenous chiefs. K̓áwáziɫ (Marilyn Slett), president of the nonprofit Great Bear Initiative Society and chief councilor of the Heiltsuk Tribal Council, read out the Great Bear Sea Declaration, with then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and then DFO Minister Diane Lebouthillier on either side.

“If you find ways to work together, you can achieve more,” Masson says. “A collective decision that we all agree on is going to be stronger than an individual decision.”

“We will work in the spirit of reconciliation, respect, and partnership,” Slett read, “to uphold and demonstrate world-leading models of collaborative governance and Indigenous-led conservation—for the future of this coast and for the benefit of all.”

The Great Bear Sea deal secured $335 million for the MPA network through a similar funding model as its prequel, the Great Bear Rainforest agreements. Representatives from Canada’s federal government joined provincial and Indigenous leaders on stage for this announcement. It was the first tri-government agreement of its kind in Canada—and maybe the world. “Back in 2005, all we asked for was to be recognized as a government, and now we are,” Neasloss said on that historic June day. Talking with me later, he added, “I think more people are starting to see that we’re not going anywhere. … By combining forces, we’re going to have the strongest protected areas out there.”

During my week-long visit to the Great Bear Sea, I glimpse what the future of this region might look like. Heading out on Ksm Wüts’iin each day, I feel like I’m on a safari in a marine park—watching humpback whales, searching for spirit bears, and paying respect to ancient pictographs painted more generations ago than I can count. But unlike many parks of the past that excluded Indigenous peoples, First Nations are ever present here. Members haul up crab pots, count the tens of thousands of salmon that still migrate up some creeks, track boats to watch for illegal activity, and operate tourism businesses to share their culture. And the underwater spectacle is as stunning as the scenery above.

One morning, Ksm Wüts’iin visits q̓áuc̓íwísuxv (Lophelia Reef), the only known live coral reef in the Canadian Pacific. The cold-water corals here lie out of sight, at a depth of 200 meters (656 feet). As we drift above them, I imagine the lattice of pink and white coral below teeming with octopuses, fuzzy crabs, and rare glass sponges. No one knew this reef existed until 2021, when a deep-sea ecologist from DFO worked with Kitasoo Xai’xais and Heiltsuk knowledge holders to track down the site using underwater robots. It was a perfect example of Western and Indigenous science working in tandem, and it led to a 2024 ban on prawning and long lines in the area.

Yet despite existing within the Great Bear Sea and, specifically, the forthcoming Central Coast MPA, Lophelia Reef was protected under DFO’s sole authority, illustrating the complexity of managing this vast seascape. The MPA network is being cobbled together by various agencies with different jurisdictions—using both Canadian and Indigenous legal tools, and featuring a patchwork of different protection levels. “We’re building the plane as we’re flying it,” says Cripps.

The lack of a model has challenged planners. Take, for instance, the issue of Indigenous harvesting. Neasloss and leaders from other First Nations insisted that Indigenous subsistence and ceremonial harvests continue in protected areas—the two have never been mutually exclusive—but DFO has historically drawn a hard line between harvesting and conservation. “In the past, the department took the position that all fishing had to be closed, rather than just some of it,” says Brenda Gaertner, a lawyer who helped negotiate the agreements. The two parties eventually compromised to not ban subsistence fishing outright and to strive for consensus around any restrictions, but other disagreements persist and have slowed negotiations.

Another part of the complexity stems from the fact that commercial fishing is worth half a billion dollars in the Great Bear Sea, employing Indigenous and non-Indigenous harvesters alike. Banning fishing entirely would have stopped negotiations in their tracks, so the current plan is for large swaths of the Great Bear Sea network to remain open to some commercial fishing. “We’re not shutting all fishing down,” says Santana Edgar, Kitasoo Xai’xais community marine planning coordinator. “Instead, we’re trying to ensure that we can continue to fish for food in a respectful and sustainable way.”

The science is clear that more robust protections lead to higher fish abundance, body sizes, diversity, productivity, and resilience to climate impacts. But partial protections can be useful too, especially if they limit the most destructive types of fishing, says Alejandro Frid, a fisheries ecologist who has spent more than a decade studying marine species alongside the Central Coast nations. Ensuring that a significant portion—ideally more than the stated minimum of 20 percent—of the total MPA network is highly protected will be key, Frid adds, as will enforcement by Indigenous guardians and federal authorities. And using local knowledge to focus protections on the most ecologically or culturally important areas while still allowing the economy to hum on elsewhere is vital to striking a balance.

On the last day of my visit, Cripps takes me to an area of scattered islets called Nowish. Chosen for its abundance of species along with its strong currents, it is one of the proposed high-protection zones in the Central Coast MPA. No one except for Indigenous subsistence fishers will be allowed to harvest fish or crabs or anything else from these waters. In oral history, the islets represent the guts of the sea monster that the animals defeated by working together from their canoe. When the sea monster surfaced, they pushed a spiky raft down its throat, causing the monster to thrash about and die. Ultimately, its entrails drifted to this site. Today, the tree-tufted rocks, striped in black and white tide lines, anchor underwater habitat for halibut, sea urchins, geoduck, and northern abalone.

Protected areas like this are especially helpful for less mobile creatures like clams, sea cucumbers, and abalone—known as broadcast spawners, Cripps tells me. These animals release millions of eggs and sperm into the water column to be fertilized and resettled. A single protected area may not be enough for such populations to find purchase, but a series of protected areas could help restore individual species and entire ecosystems. Cripps points out the direction in which we’re drifting on the boat’s map, and I picture an underwater highway flowing south—an unseen corridor carrying eggs, larvae, and nutrients from one ecological hotspot to the next, seeding ecosystems and feeding communities.

As night falls in Kitasoo Xai’xais territory, members of the stewardship team gather at Neasloss’s place, a boxy two-level house up Mountain Goat Road. When I arrive, Cripps is in the kitchen frying red snapper caught that day, while everyone else is decompressing in the living room, surrounded by Indigenous artifacts from around the world, from Australian boomerangs to a Coast Salish drum. A portrait of a white spirit bear, taken by Neasloss, watches from above the TV.

Seated in a leather recliner, Neasloss has just returned from Ottawa, Ontario, where he met with Canadian ministers about the need to weave Indigenous knowledge into federal policy and legislation. By the look of his left foot tapping the wood floor, I get the feeling the meeting didn’t go well.

“It’s frustrating,” he says. “We have to fight every step of the way. How can we change management if we can’t change the rules at the top?”

He’s referring to legislation such as the 157-year-old Fisheries Act, which is nearly as old as the Constitution of Canada. Both of these decrees give the federal government immense power, which is always looming on the horizon like a storm that’s hard to see beyond. But on sunnier days, Neasloss can zoom out to view the wider path to co-governance. It’s been a long, nonlinear journey, but nations have managed to pass many obstacles and get to the other side of serious storms. Despite some choppy patches, the current is flowing in the right direction.

Soon, the Central Coast nations will declare additional Indigenous protected areas to underscore their own laws and authority. Soon, they’ll announce an Indigenous name for the Central Coast MPA that will appear on maps, surrounded by colonial names. And just as they invite me to sit down and share red snapper from the nearby sea, they’ll continue to set the table, again and again, for any willing government or partner that recognizes them as equal.

People on this coast know that the only way to defeat a monster and find a passage to a better future is to stay in the canoe and paddle forward. Together.

This story was made possible in part by an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, as well as support from the Tula Foundation.

This article first appeared in bioGraphic, and is republished here with permission.