On a Saturday in mid-May, curtains of mist drifted across Seattle as some 200 aspiring changemakers descended on a once-abandoned steam plant on the city’s South End for day one of a weekend conference. The goal? To learn how new kinds of financial vehicles could move funds away from initiatives that harm environments and communities, and toward efforts that restore them.

Regenerate Cascadia convened the “Cascadia BioFi Conference,” the first-ever assembly of its kind, at the Georgetown Steam Plant. The venue choice was intentional, as the structure sits half a mile from the Duwamish River, a waterway that once ran through nine miles of wild bends and floodplains before the city dredged and straightened it in the 1910s to create a five-mile canal for industry. Today, nearly 80 percent of the city’s industrial lands sit in the reshaped river valley, a site of both industrial violation and collective reinvention.

After a series of opening remarks, Brandon Letsinger-Brown, co-administrator of Regenerate Cascadia, oriented the audience to where they are, the Cascadia bioregion, while regenerative designer Michelle Lee followed by defining “bioregional finance,” or BioFi, a term first coined by Samantha Power in 2024, when Power founded the BioFi Project to further develop its core concepts.

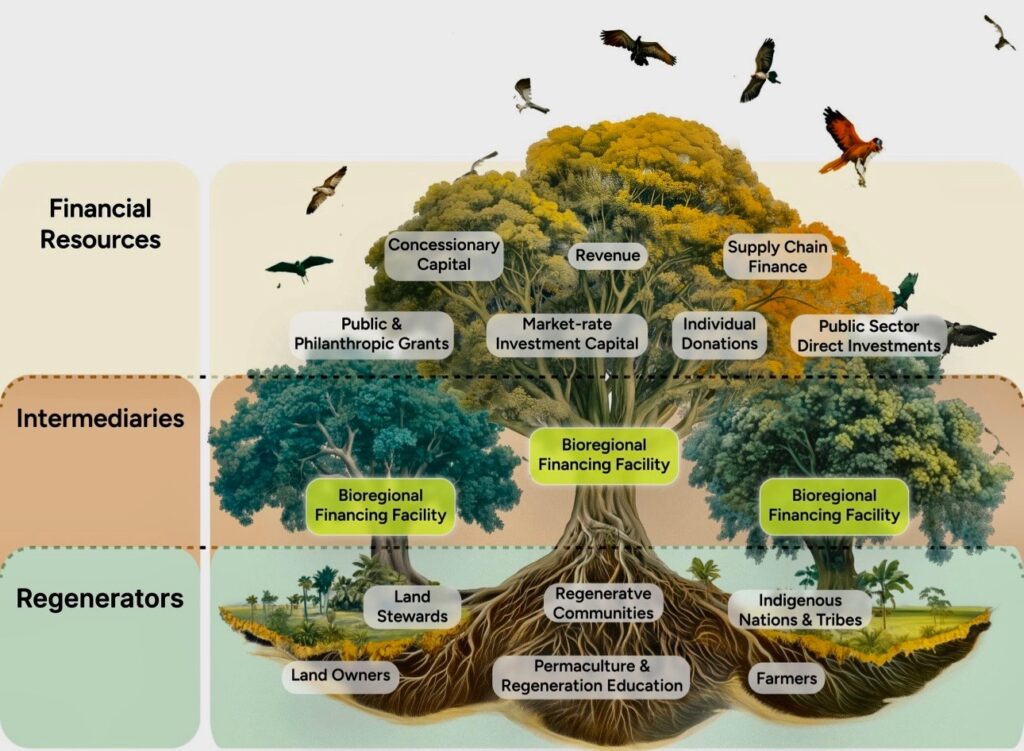

Bioregional finance is both heady and simple: For a bioregion to regenerate its lands and waters, those who live there need money, and they need institutions that can funnel that money to people primed to do the work. To do this, the BioFi Project has begun to develop what Power calls “bioregional finance facilities,” funding vehicles that can bridge the divide between institutions with wealth and groups on the ground without access to capital.

Most attending this BioFi conference see the movement as a critical lever for structural change, not just a philosophy but a practical way to organize people and economies at every level. Everyone there appeared to be seeking ways to better attract resources and turn rhetoric into action.

Lee, through her work as a principal of the BioFi Project, supports this ambitious work. During her presentation, she gave three examples of groups in the West developing these “bioregional finance facilities.”

Re/Village Green Valley works in Graton, California, where it aims to use both a nonprofit trust and a public benefit corporation to build new community hubs in their small Northern California town. The immediate focus of Re/Village Green Valley is the park and town square it hopes to develop on the site of a former gas station. It needs to raise $1.5 million to make its vision of stage and marketplace, pollinator gardens and play areas a reality.

Regenerate Cascadia has a far grander vision. Letsinger-Brown founded Regenerate Cascadia with Clare Atwell in April 2023 to coordinate resources and support the work of restoring the bioregion. That fall, the team embarked on a listening tour through 14 communities, from Oregon to British Columbia, meeting with nearly 1,000 people to discuss what it would take to create a unified movement to restore ecosystems and communities. Having synthesized that data, Regenerate Cascadia focuses on two key initiatives: building relationships with and between groups of varying sizes doing place-based restoration work across the region, and building an ecosystem of funding to support these groups.

When asked what it means for Regenerate Cascadia to be a bioregional finance facility, Letsinger-Brown said, “it might take us a couple more years to figure that out.” Without a blueprint for the best practices of bioregional finance, they’re still experimenting with alternatives as they search for the ideal way to build these new institutions.

Salmon Returns expressed similar challenges. Founded in February by Donna Morton and Cheryl Chen, Salmon Returns is a bioregional fund focused on directing finances to local communities and grassroots organizations throughout Salmon Nation, what Chen called a “kin bioregion to Cascadia,” during her talk at the conference. Cascadia, she told the audience, is nested within Salmon Nation, an area “defined by the traditional extent of wild Pacific salmon.” Recognizing that only 3 percent of global capital is held by philanthropic institutions, Chen and Salmon Returns are concerned with how to use philanthropy to unlock the other 97 percent.

Most attending this BioFi conference see the movement as a critical lever for structural change, not just a philosophy but a practical way to organize people and economies at every level.

Their work focuses on helping communities build local regenerative economies that offer people a sense of self-sufficiency, self-determination, and shared responsibility through food hubs, healing centers, housing cooperatives, and renewable energy microgrids. To make this real, Salmon Returns aims to raise $15 million by the end of 2027. From that, they intend to create loans with low- or no-interest terms, so they can reinvest those funds without extracting profits into partner organizations in the region, like the Okanagan Indian Band in British Columbia.

A core challenge faced by these funding models emerges from the fact that, as Lee said, these instruments “work at the speed of trust.” While this approach helps ensure that bioregional finance facilities won’t extract resources from the communities they support in the way traditional financial institutions do, it also has the potential to unintentionally exclude others from receiving support since, in some of the funding models discussed during the conference, resources are restricted to those already in the funder’s networks.

This is a cause of concern, given that bioregionalism has historically struggled to be a space of meaningful inclusion. In 1988, after the Third Annual North American Bioregional Congress, a journal was published to document the proceedings, and it included a conversation between three non-white attendees called “On The Authentic Inclusion of People of Color.” In it, Jeffrey Lewis, a Black man, said that bioregionalism was “primarily a movement of middle-class, educated white folks.”

For future assemblies to effectively reflect, represent, and serve the diverse communities that inhabit the bioregion, Regenerate Cascadia and its partners remain tasked with building lasting, authentic relationships with all communities of color. Its organizers will continue to foster trust with the communities they want to reach, to understand the day-to-day realities facing them, and then act accordingly.

Chen and others are determined to see change, highlighting that the BioFi organizers have a clear desire to pursue more meaningful and constructive relationships with people of color and Indigenous communities, and as they do, these spaces will grow more inclusive and representative. The conference this spring was, after all, the first of its kind.

“It’s really brave,” Chen said. “And that’s why I admire Regenerate Cascadia for putting on this conference.”

In all, the BioFi gathering afforded roughly 200 people a place to organize around similar values, build relationships, exchange ideas, and co-vision how to reimagine investment strategies for a livable planet and a regenerative, equitable future.

Disclosure: Cheryl Chen is a founding partner of Salmon Nation Trust, a close partner of Magic Canoe, the founder of Salmon Nation CoLabs, and was a founding member of Magic Canoe.