This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, regenerative economy we need from Alaska to central California. Find out more about this project and its funders, Magic Canoe and the Salmon Nation Trust.

Bahram Rashti was hungry for some arugula. Spinach and lettuce, too.

Having landed in Haida Gwaii to start a clinical rotation in dentistry, Rashti headed to a grocery store to stock up on the salad fixings he was used to tossing in his shopping cart in places he’d lived before.

Born in Ottawa, he attended McGill University in Montreal and in the late 2000s moved west for a residency at the University of British Columbia and Vancouver General Hospital.

Then it was on to Haida Gwaii, an archipelago of islands home to some 4,400 people, located 720 kilometers northwest of Vancouver and about 100 kilometers off the B.C. coast. In the remote towns of Masset and Skidegate, Rashti found the greens he was looking for at the local grocer. But they were flimsy, soft, and not going to last very long in the fridge before going bad. And then he saw the price — way higher than he expected.

“It was shocking at the time,” said Rashti. “Not only did we have to pay more, but you got very low shelf life as well as freshness.” Rashti was coming to realize what folks living in more remote areas of B.C. know too well. Long distances from food growers and processors drive up prices and can make some key sources of nutrition hard to get.

Grocery prices tend to be two to three times more expensive in northern Canada. The northwestern part of B.C. that includes Haida Gwaii has the highest food costs in the province, according to a 2023 report by the BC Centre for Disease Control.

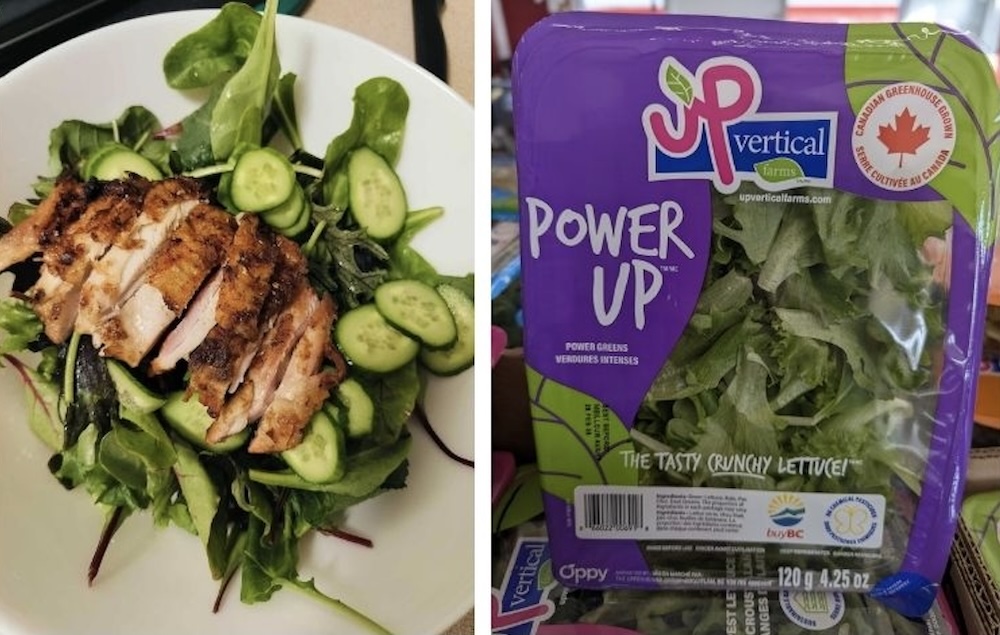

Rashti is no longer a dentist, but he’s acting on what he learned in Haida Gwaii. Today, he is CEO of UP Vertical Farms, a Pitt Meadows-based farm that grows leafy greens in nine or more vertically stacked layers in a climate-controlled setting.

The shift makes sense, Rashti says, because he entered health care to “make things right.” That applies whether fixing a chipped tooth or blocked access to healthy fresh produce.

Rashti co-founded UP with his brother Shahram two years ago. “We said, ‘Let’s do it — big enough to not just feed B.C., but for Western Canada, and eventually all of Canada.’”

If that sounds ambitious, the operation lately has received a boost from an unlikely source — Donald Trump, whose tariff threats and general hostility towards Canada has triggered a surge in buy-local sentiment in Canada.

“It’s almost doubled our production and more than doubled our retail presence,” Rashti said.

To meet that rising demand, UP has expanded by nearly a third in recent months and now employs about 45 people, according to Rashti.

UP is partnering with Costco, Safeway, Save-On-Foods and other grocers big and small to get its salad kits and other products to market.

Leaving the lights on

Farming in controlled environments like greenhouses is nothing new. Nor is the term “vertical farming” — popularized by a Columbia University professor in the 1990s to describe growing produce indoors in stacked layers and rooted in hydroponic solutions rich in nutrients rather than soil.

Vertical farming started to take hold throughout Canada and the United States in the late 2010s.

Tech advances keep moving the line on how efficiently vertical farming can be practised. The invention of LED lighting, for example, has made a huge difference because “you could create the right wavelength of light” for optimal growing conditions “at pretty low energy costs that make leaving the lights on all winter more feasible from an economic perspective,” explained Evan Fraser, director of the Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph.

The plants themselves have been tinkered with continually in the lab to thrive in hydroponic settings, according to Fraser.

Today’s “continuum of technologies” used in vertical farming means “all the environmental variables are basically under the control of the farmer. You’re not relying on nature at all,” said Fraser.

At UP, for example, crops are grown hydroponically in rooms that mimic different weather conditions. Plants germinate in the dark before moving on to racks to grow under LED lights. The plants are then harvested and bagged for distribution.

As UP’s Bahram Rashti explained to a trade show publication in December, his company is as much about engineering as it is about nature.

“We design, build, and operate our plant factories in a turnkey fashion, which enables us to customize and build exactly what is needed for a fraction of the cost.” UP automates aspects of “irrigation, seeding, growing, harvesting and packaging, in turn minimizing human intervention and reducing labour costs while also maintaining hygiene.”

Rashti claims the company’s “game-changer” techniques enable “consistent, high-quality yields all year round with 99 per cent less water, nutrient fertilizers, and land compared to traditional farming.”

If that sounds like a spaceship landing amidst one of B.C.’s traditional farm belts, UP is welcomed by Pitt Meadows Mayor Nicole MacDonald, whose city’s land is mostly devoted to agriculture. “We encourage innovations like UP Vertical Farms that help evolve and contribute to the viability of our local and regional food systems,” MacDonald said.

Benefits include water, pesticide and energy savings

Advocates of vertical farming say it’s a compact response to climate change because it conserves water and cuts fossil fuel energy used to transport food long distances. Compared with regular farming, “the carbon footprint is vastly lower as long as you’re using green energy,” said Lenore Newman, director of the Food and Agriculture Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley.

Others note that indoor farming slashes fertilizer and pesticide use by literally shutting the door on most pests.

Trump’s trade warring underscores the fact that more than half of Canada’s fruits and vegetables are imported. Food insecurity previously was steadily rising in Canada, and the implications for local resiliency were not lost on the Rashti brothers.

“We realized we had a problem,” Bahram Rashti said. “Eventually, those countries exporting will reach a point and say, ‘We’re going to feed our people first instead of exporting,’ and either there is going to be shortages or price increases.”

Vertical farming does have its critics, however.

Local agriculturists fear that the tech-based form of farming shifts production from local farmers to investors looking to make a buck. The recent volatility of the market does suggest a cause for concern.

To date, the trajectory of vertical farming has been anything but straight up.

Throughout the 2010s, vertical farms opened in San Francisco, Toronto and Guelph, among other places across North America.

But in recent years a lot of high-profile vertical farm corporations have shut down, with high energy costs and rapid expansion among the reasons for failure.

One such enterprise in California named Plenty made headlines this year when it filed for bankruptcy a decade after launching. Pundits blamed the company’s unrealistic emphasis on growth and returns.

It’s a trend that Fraser has noticed in a lot of the bigger U.S. operations that were backed by venture capital funds. “The sense I get is that they didn’t fully appreciate the complexity of natural systems like growing biology,” Fraser said.

So who’s still in the game and setting the pace? GoodLeaf Farms, which started producing local greens in Halifax in 2011, has become the largest vertical farm in Canada, with locations in Guelph, Calgary, and Montreal. The latter two operations opened within the past two years and aim to produce over two million pounds of leafy greens each per year.

South of B.C.’s border, a vertical farm in Washington state was named vendor of the year in 2022 by the Washington Food Industry Association, a state-run organization that promotes and protects independent growers. NW Farms produces six million heads of lettuce annually and grows six different kinds of lettuce with 90 per cent less water than traditional farming.

Fraser estimates that it costs about $30 million to build a vertical farm. That’s a lot of investment given that, as Fraser noted, Canadian vertical farms face a relatively small Canadian market. The cost of land and permitting are other obstacles, he added.

UP has put “millions” into building their business, Rashti told the Vancouver Sun in 2023.

They started with a two-phased approach. UP has space to grow leafy greens on 16 racks. But the company has used only nine since its inception, which currently gives them capacity to grow about 6.3 million bags per year. UP is producing just shy of that target as of this June, according to Rashti. He hopes to launch the second phase — utilizing the remaining racks — within the next year, which he said would nearly double UP’s production.

Rashti said this rate of growth has ensured UP hasn’t been swamped by water and electricity costs.

Newman credited the decision. “They’ve trial-and-errored and now they’re doing pretty well, I think we’re going to see continued growth from them,” she said.

Fraser expects to see more breakthroughs leading to more types of food people can get from vertical farms. “There’s a job for plant breeding to create the varieties of fruits and vegetables which will be suitable for hydroponic and growth solutions under LED lights,” he said.

That fits Rashti’s hopes. He would like UP to move into growing fruits and vegetables, and to exporting more to U.S. states in the Pacific Northwest.

UP exported to the United States before the tariffs were implemented but is reviewing that plan. Whether the United States and Canada iron out their trade disagreements sooner or later, Rashti remains optimistic.

As overhead and technology costs fall, outfits like UP will multiply, he predicted. “I think the next generation of Canadians and people all over the world will be used to eating products coming out of vertical farms.”